The Day the Dollar Lost Its Gold: The Nixon Shock

On August 15th, 1971, U.S. President Richard Nixon ended the dollar’s convertibility to gold, bringing an abrupt end to the last vestige of the international gold standard.

Why? And what led up to this? Let’s dive in.

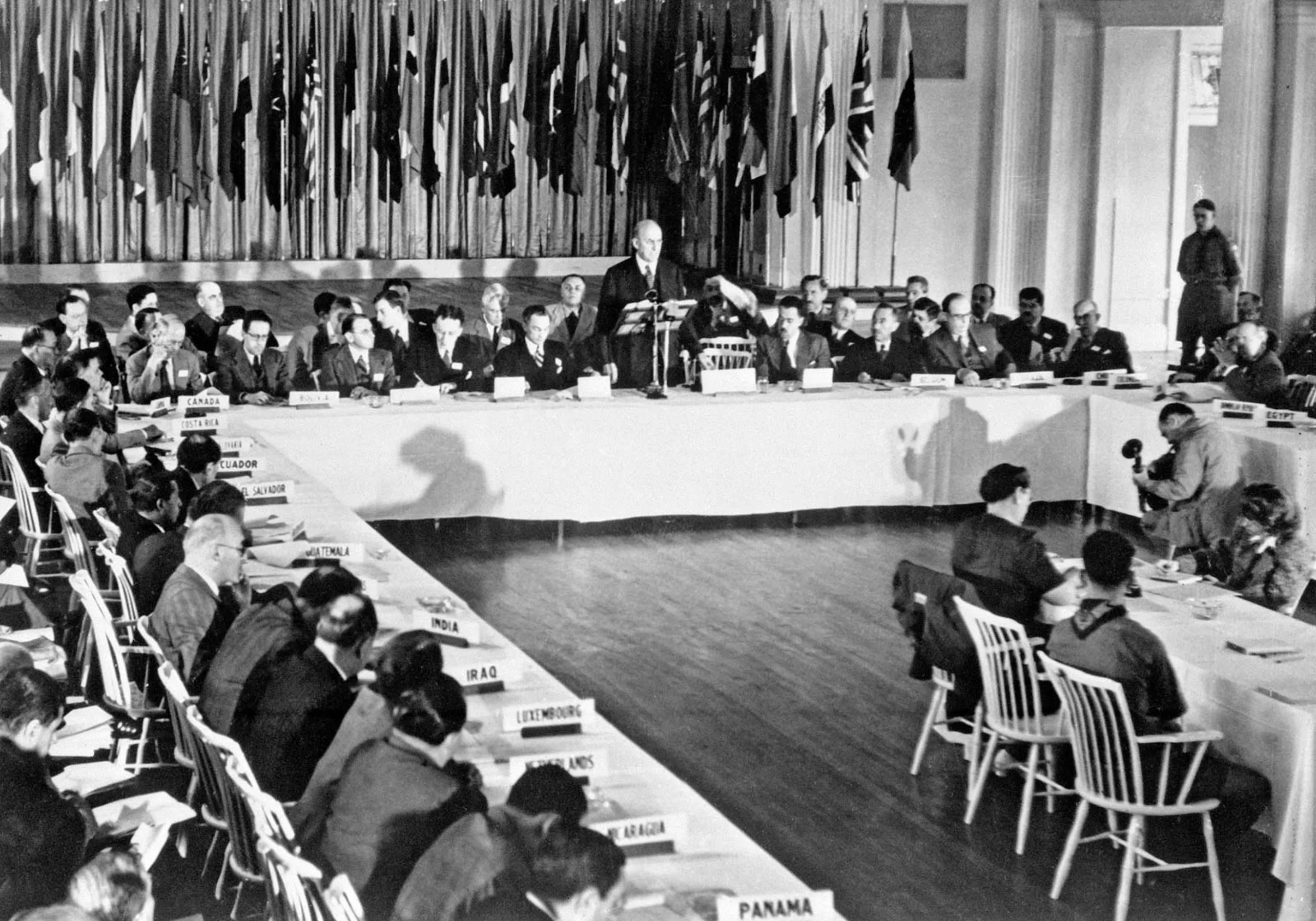

Context: Bretton Woods

In 1944, as the second World War came to an end, 44 Allied nations met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to design a new global monetary system — one that would attempt to prevent the currency chaos and competitive devaluations that had helped fuel the Great Depression and World War II

The result was the Bretton Woods system. The United States would peg the dollar to gold at $35 per ounce, and every other country would peg its currency to the U.S. dollar. For example, Japan fixed its exchange rate at ¥360 = US$1.

This made the U.S. dollar the anchor of global finance — and gave the United States an extraordinary degree of economic influence. In return, it would maintain the dollar’s value to gold, and not print more money than it could back with gold.

The U.S. emerged from the war with more than half of the world’s official gold reserves and a booming economy. Through what became known as the Marshall Plan, it extended roughly $13.3 billion in aid to a devastated Europe — money aimed at rebuilding industries, preventing famine, and stabilizing currencies. The program also had a strategic purpose: fostering economic stability to counter the spread of communism. Much of that aid ultimately flowed back into American exports, as European nations used the funds to buy U.S. goods and machinery to rebuild.

Dollar Outflows: U.S. Spending

It worked at first. The world started to recover from the second World War. However, as the decades wore on, the U.S. began spending money it couldn’t afford, and the strain on the Bretton Woods system mounted.

Trade Deficits Begin Emerging

As the world recovered from WWII, Europe and Japan began exporting more goods, with the United States as the biggest buyer. During Dwight D. Eisenhower’s presidency (1953–1961), U.S. Dollars flowed out to pay for imports while little came back from exports, pushing U.S. currency into foreign central banks.

Overseas Military Commitments

Under Eisenhower and later John F. Kennedy (1961–1963), the Cold War made overseas spending a necessity. The rivalry with the Soviet Union wasn’t fought directly but through alliances, aid, and influence. The U.S. funded NATO in Europe, maintained bases in Japan and Korea, and poured economic and military support into allies to contain the spread of communism.

By the mid-1960s, under President Lyndon B. Johnson (1963–1969), this strategy extended into Southeast Asia in what would become known as the Vietnam War. What began as limited U.S. backing for South Vietnam in the late 1950s under Eisenhower and Kennedy grew into a full-scale military commitment. Funded through deficit spending, this sent even more dollars abroad.

The Great Society Programs

At home, President Johnson launched his ambitious “Great Society” agenda — Medicare, Medicaid, education funding, and anti-poverty programs. Federal spending surged, but taxes didn’t rise to match, which meant more borrowing and monetary expansion.

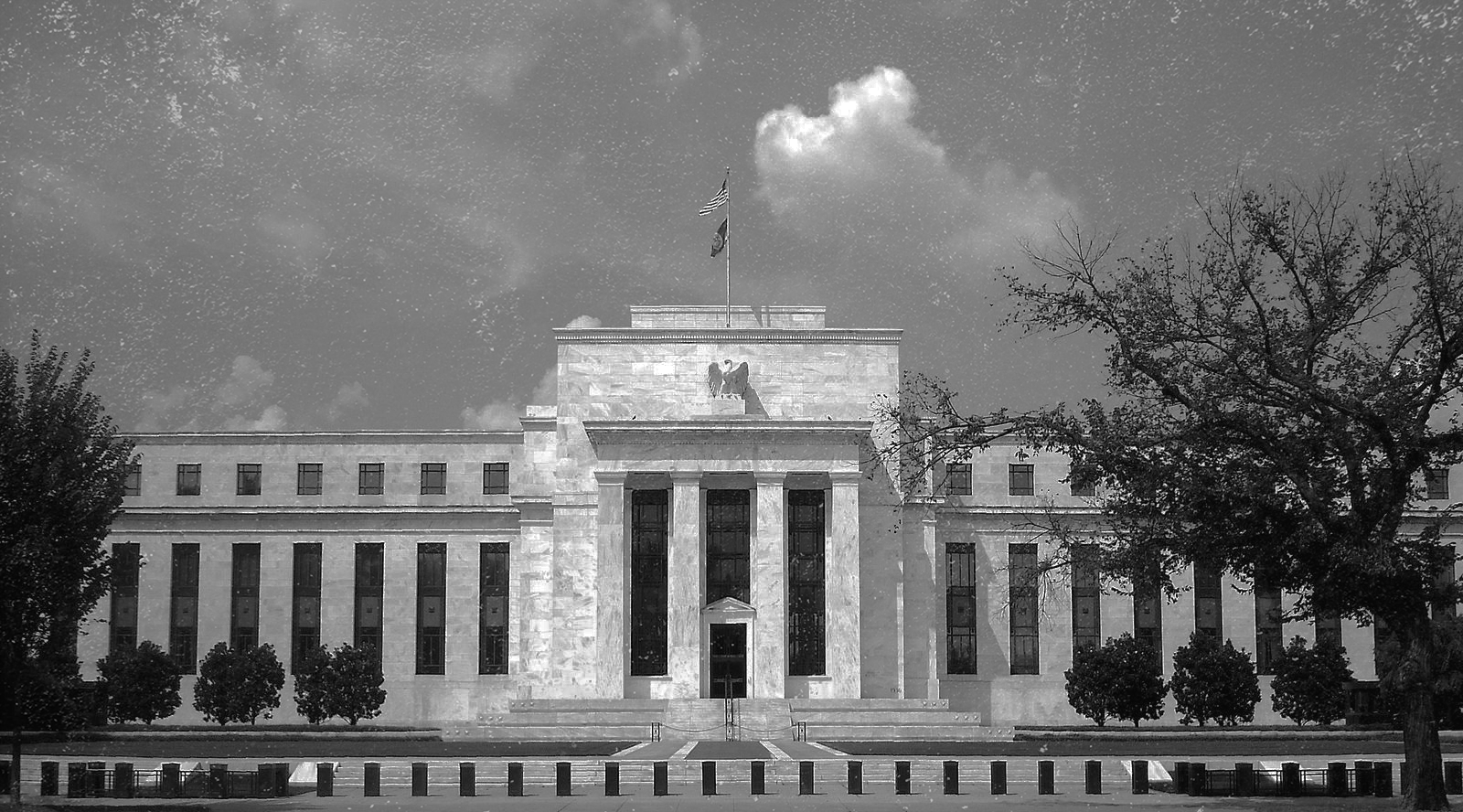

Start The Presses

Facing expensive domestic agendas, overseas commitments, and growing trade deficits, the Federal Reserve leaned on “easy money” in an attempt to keep the economy growing. Under both President Lyndon B. Johnson (1963–1969) and President Richard Nixon (1969–1974), the Fed was actively injecting new money into the system to cover the ever-growing costs of war and social programs, expanding the supply of dollars while keeping interest rates low to encourage borrowing and investment.

This monetary expansion outpaced the U.S.’s gold reserves, leaving far more U.S. dollars in circulation than Fort Knox could ever redeem at $35 an ounce — much of it accumulating in foreign central banks.

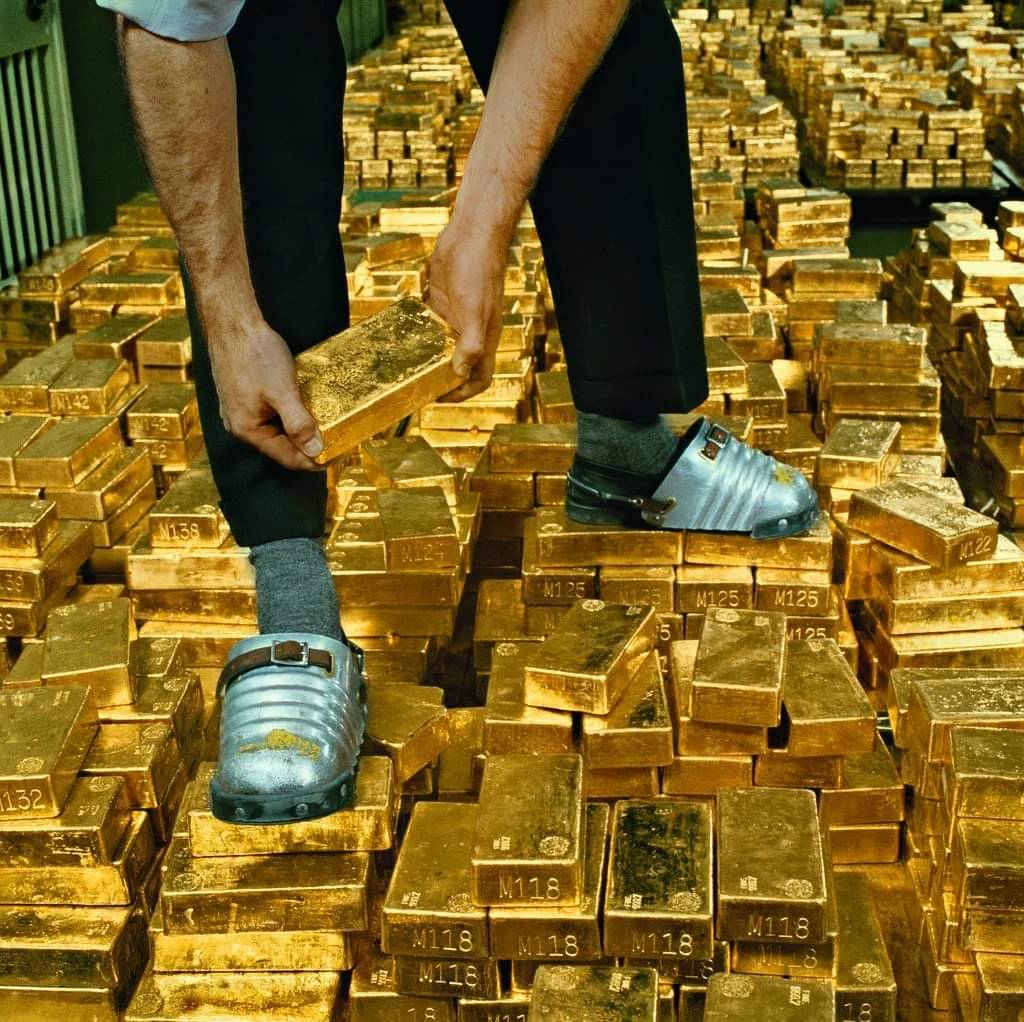

Take your greenback, I’ll take my gold back

The world saw what the U.S. was doing. Increasing money supply, with no increase in gold reserves. As confidence in the dollar eroded, countries began redeeming their dollar holdings for physical gold instead of holding paper. The pressure reached a breaking point in 1968 with the collapse of the London Gold Pool. The Pool was one of the key mechanisms used to keep gold fixed at $35 an ounce — a coordinated effort where the U.S. and major Western central banks pooled their reserves to buy or sell gold and defend the $35/oz peg.

The U.S. gold stock was already under strain, and the Pool was forced to sell ever-larger amounts of bullion into the market to maintain the $35 price. In March 1968, redemption demand spiked beyond what the Pool could cover, forcing its shut down.

U.S. gold reserves continued to dwindle, while billions of U.S. dollars sat in foreign central banks — all theoretically convertible into gold at $35 an ounce. Something had to give: either America’s gold, or the system itself.

The System Gives Way

On August 15th, 1971, U.S. President Richard Nixon announced the suspension of the dollar’s convertibility into gold. This “temporary” measure was meant to stabilize the U.S. economy and stop the run on American gold reserves. In reality, the gold window was never reopened. The Bretton Woods system was effectively dead overnight.

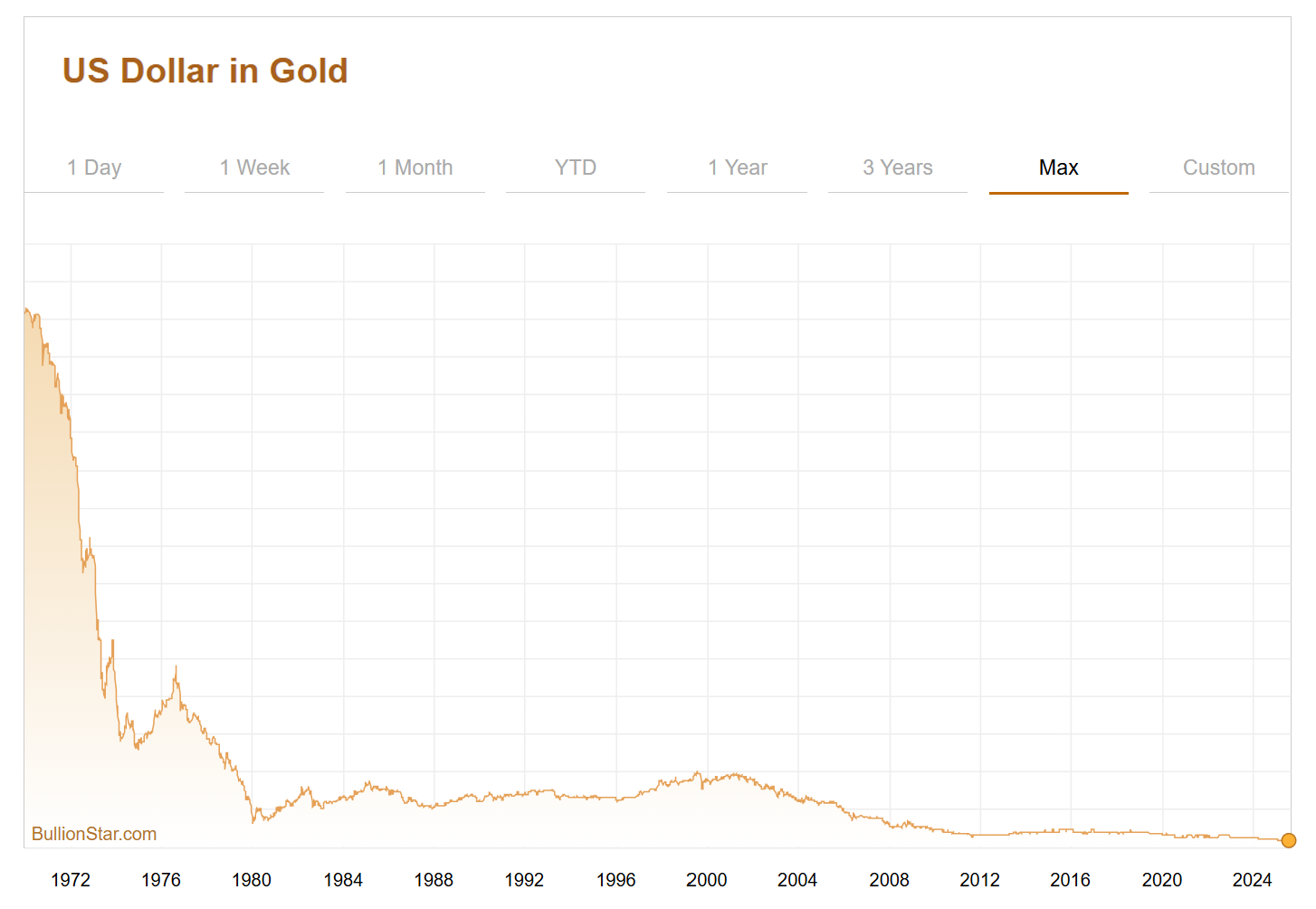

Since then, the U.S. dollar has undergone a dramatic loss in value against gold. From a fixed rate of $35 per ounce, gold has climbed to over $3,000 per ounce in 2025 — a decline in the dollar’s purchasing power of more than 98% over five decades.

Currency Devaluation: A Cautionary Tale

The U.S. dollar is not alone in its decline. The British pound, once the centerpiece of global finance, had already lost much of its strength by the time of Bretton Woods. Today, it has shed over 99% of its purchasing power since its 18th-century inception.

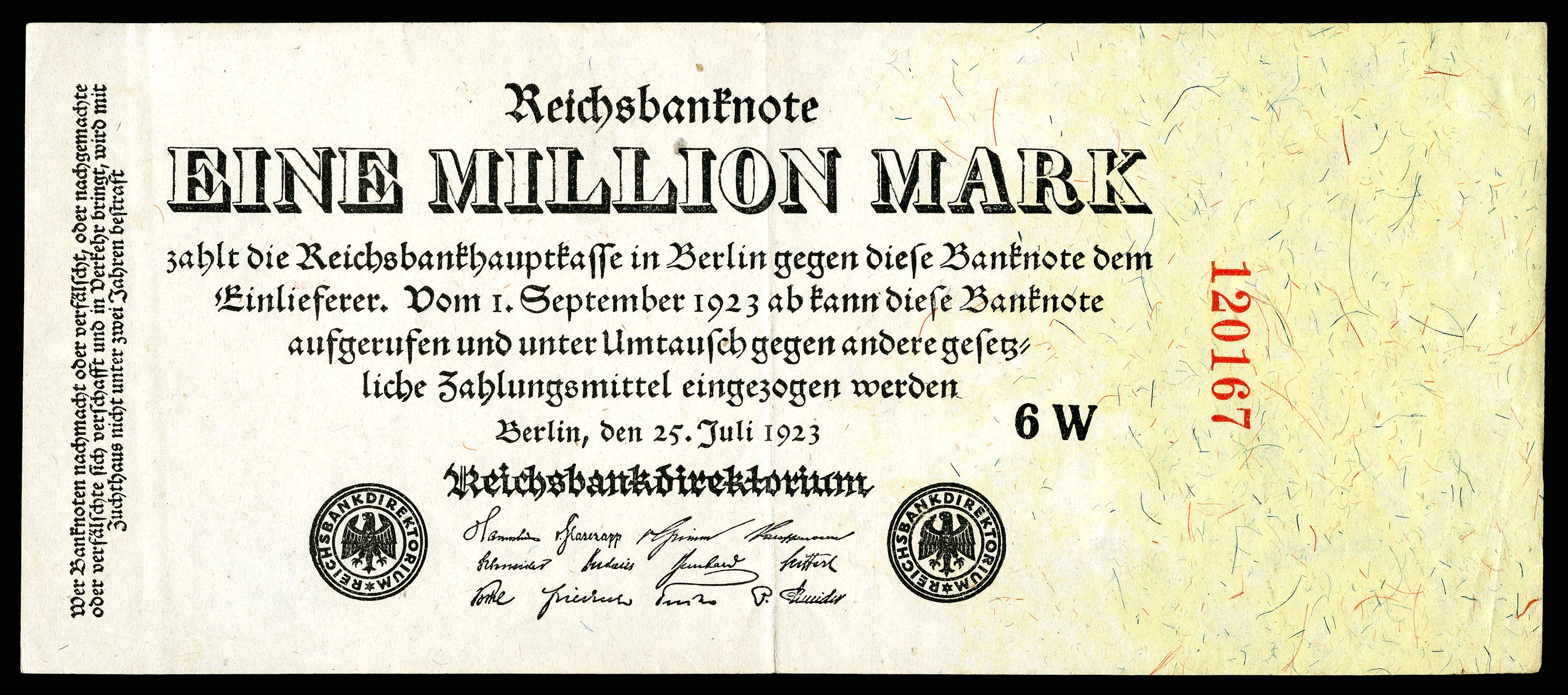

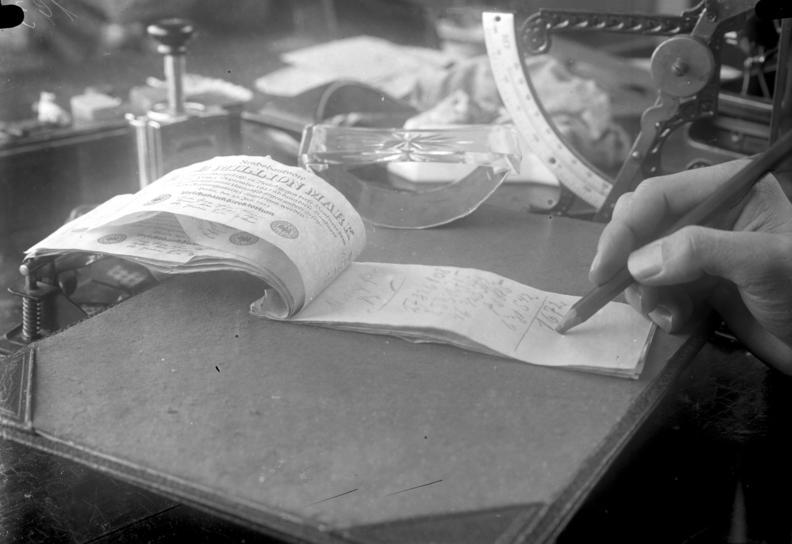

History offers other warnings. In the early 1920s, Weimar Germany printed so much paper money to pay war reparations and domestic bills that the Papiermark became effectively worthless. At the peak of the crisis, prices doubled every few days and by the end of its life in 1923, 4.2 Trillion in Papiermark was worth only US$1. Papiermark notes were used as notepads, since an actual notepad would cost billions.

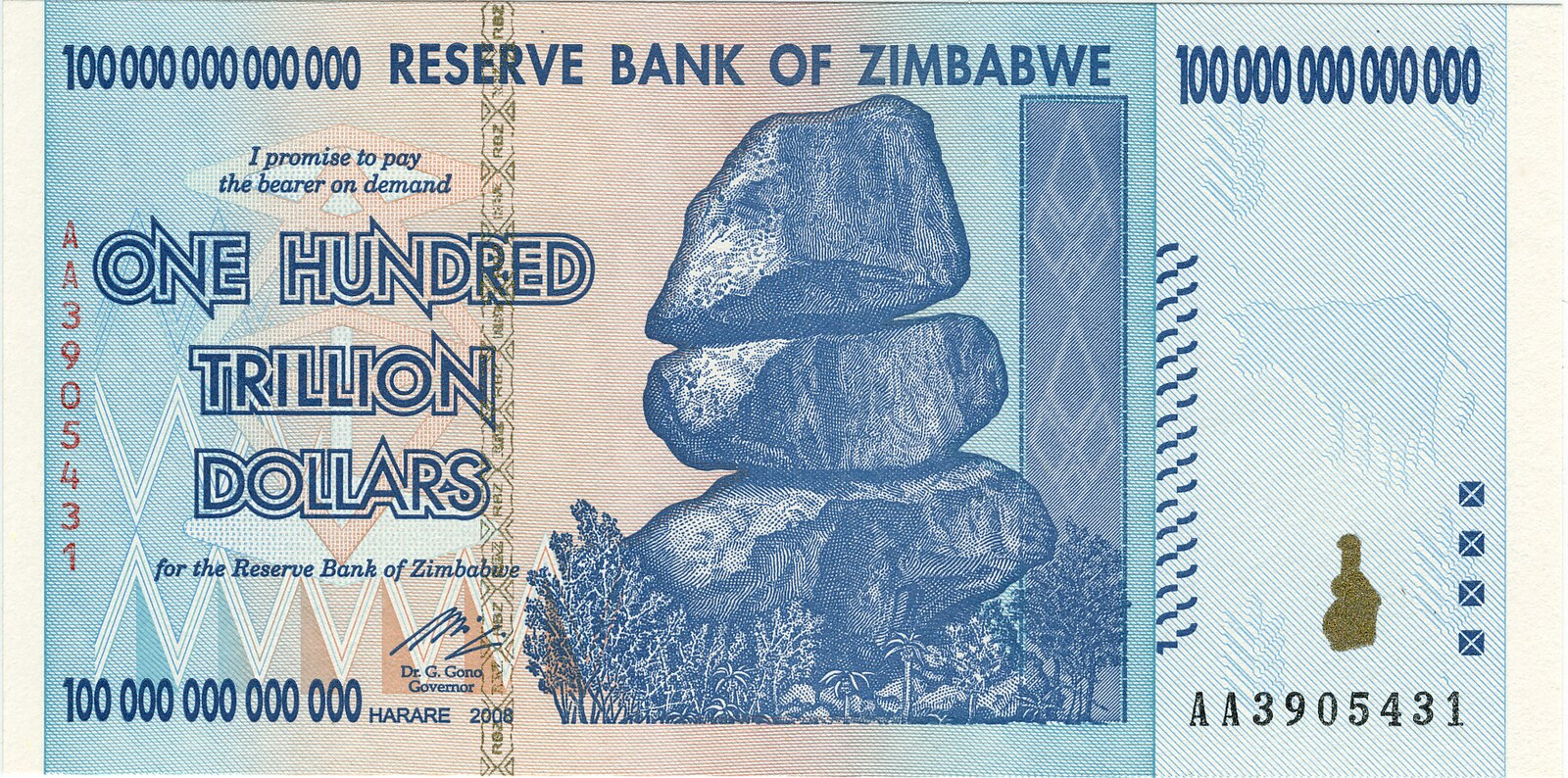

Zimbabwe’s currency collapse in the 2000s is another infamous example: by the end, the exchange rate had spiraled to roughly Z$35 quadrillion for 1 U.S. dollar. That meant Zimbabwe’s 100 trillion dollar note — once the highest denomination ever printed — was effectively worth less than half of one U.S. cent. In a striking turn, Zimbabwe has since introduced the partially gold-backed ZiG as its official currency, in a bid to restore stability and confidence by tying its money once again to something tangible.

Deja Vu

“There is no present or future — only the past, happening over and over again”

— Eugene O’Neill

Today we see familiar patterns emerging: political maneuvering, shifting policies, and spending decisions made far above and away from ordinary people. The faces, the currencies, and the reasons change, but one truth stays the same: the structures we build on paper are never permanent.

From Wall Street to The Roman Empire, monetary systems have risen and fallen. Every era believes it is wiser, more enlightened, better managed — yet history reminds us otherwise. Through it all, gold and silver have endured. They have served as real money for millennia, long before numbers on a screen, paper notes, or treasury bonds, and they remain a tangible store of value without needing anyone’s decree or “legal tender” stamp.

As geopolitical tensions rise and the U.S. dollar faces new pressures, central banks around the world are quietly turning back to gold. The search for a perfect monetary system continues, and in the meantime, perhaps the wise course is to hold on to something tried and true, tangible and real.

Check out BullionStar’s Range of Physical Gold, Silver and Platinum

Popular Blog Posts by BullionStar

How Much Gold is in the FIFA World Cup Trophy?

How Much Gold is in the FIFA World Cup Trophy?

Essentials of China's Gold Market

Essentials of China's Gold Market

Singapore Rated the World’s Safest & Most Secure Nation

Singapore Rated the World’s Safest & Most Secure Nation

Infographic: Gold Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF) Mechanics

Infographic: Gold Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF) Mechanics

BullionStar Financials FY 2020 – Year in Review

BullionStar Financials FY 2020 – Year in Review

Service Update 27/01/26 – A message from BullionStar’s Deputy CEO

Service Update 27/01/26 – A message from BullionStar’s Deputy CEO

BullionStar Announces Record Global Revenue of SGD 761.1M in FY 2025

BullionStar Announces Record Global Revenue of SGD 761.1M in FY 2025

Silver Enters 2026 in a State of Structural Breakdown

Silver Enters 2026 in a State of Structural Breakdown

BullionStar Update: Extreme Demand, Silver Supply, and Market Conditions

BullionStar Update: Extreme Demand, Silver Supply, and Market Conditions

Back-to-Back Records: BullionStar Sets New Highs in September and October 2025

Back-to-Back Records: BullionStar Sets New Highs in September and October 2025

BullionStar

BullionStar 0 Comments

0 Comments